It’s been a while since we’ve had the pleasure of the 10th Doctor’s company in this marathon; the last story was the comic, The Time Machination (in 1889) and the last TV story was Tooth and Claw in 1879. That’s, admittedly, only 30-odd years in terms of chronology, but with the 19th century being as packed as it is with Doctor Who stories (as well Sherlock Holmes and other bits), it’s seems a long time since we’ve shared his company. However, these two episodes also feature Martha Jones as the Doctor’s companion and the last time she featured in the marathon was way back in 1599, in The Shakespeare Code. That’s over 300 years since we’ve seen her!

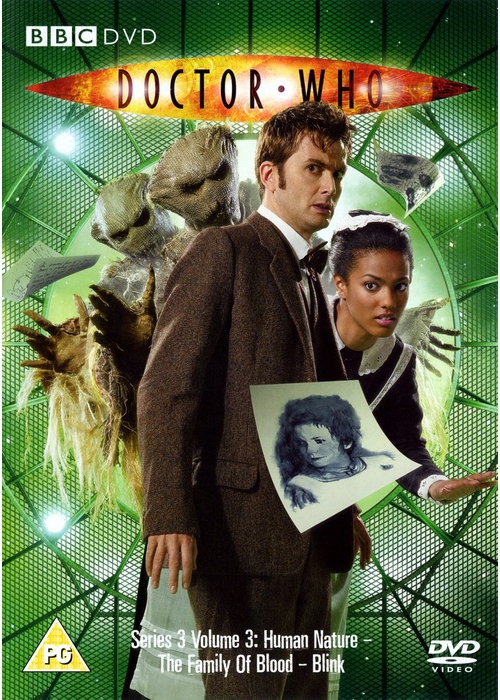

And what a cracker of a story to come back on. Human Nature, as we’re all aware, is an adaptation of one of the most highly regarded New Adventures featuring the 7th Doctor. Adapted by its writer, Paul Cornell, for the TV series, he takes the opportunity to change various details whilst keeping the core of the story the same. The Doctor becoming human and falling in love; a relentless alien species hunting him down; the onset of WW1 and a boy’s school setting are all present and correct.

I’m not sure I always appreciate ‘new’ Doctor Who on a first watch. I enjoy it, don’t get me wrong, but I’m not sure I always connect with it, on first viewing, in the same way my younger self did with classic Doctor Who. I’ll admit that the short-form version of modern Who sometimes makes me feel like stories are a little bit rushed. Therefore, it’s always a bit of a treat when I watch a two-parter where more time can be afforded to the story and it is, effectively, the same length as a classic series 4 parter. But I don’t know what else it is that leaves me feeling a bit disconnected from some of the stories.

It’s weird because when I go back and rewatch them, I find so much to enjoy I wonder what I was thinking in the first place, or why my feelings towards them is so nondescript. It doesn’t happen all the time. I remember thoroughly adoring Gridlock on first watch, and Flatline, and Under the Lake and many more, but I have to be honest and say, lots haven’t really stuck with me. I supppose one issue is that my feelings towards classic Who are tied up with so many other emotions of my teenage years (and my early twenties), identifying who I was as a person, having my own personal space where I would watch, rewatch and rewatch again, classic stories; having a circle of friends who also loved Doctor Who and fuelled that fire. I think I was exploring the series and always finding out new things and misunderstanding some things. In those early days of the internet when every piece of information about Doctor Who wasn’t at the touch of my fingers, I think it all seemed a bit more magical than it does now.

That’s why I’m glad I’m doing this marathon (and randomly watching other episodes alongside) because I’m rediscovering the joy of modern Doctor Who. I go around these forums staunchly defending that it’s the same series as classic Who all the while having a little voice in the back of my head not quite agreeing with myself.

But then I watch Human Nature and The Family of Blood and that little voice can go sod off. It’s absolutely brilliant.

First and foremost it highlights what a good actor David Tennant is. Having not watched any 10th Doctor stuff for quite a while, I hadn’t noticed how ‘different’ his portrayal of John Smith is from the 10th Doctor. It’s only when the 10th Doctor ‘returns’ at the end of the story, that the difference is thrown into sharp relief. It’s a lovely performance of a simple man, falling in love but knowing something isn’t quite right with his life.

But Tennant being great all by himself wouldn’t elevate this story to the heights it achieves. Jessica Hynes and Freema Agyeman match him scene for scene in how good they are in their roles as Joan Redfern and Martha. Freema, in particular, has a difficult job of portraying Martha,, as usual, but also acting as Martha acting as a lowly maid. I love the scene where she realises that Jenny has been taken over by the Family. Her dawning realisation is quite chilling (assisted by Rebekah Staton giving an unsettling turn as the possessed maid). Jessica Hynes upstanding Nurse Redfern has a great chemistry with Tennant’s Smith and it’s heartbreaking when she realises she has to let him go so that the Doctor can return to save the world. Her distaste towards the Doctor at the end, claiming Smith to be the braver man as he was willing to die to save the world, is another great scene.

And outside this core trio, there is a superb supporting cast. The aforementioned Rebekah Staton is great as both Jenny and Mother of Mine. Thomas Sangster is great as Latimer as is Tom Palmer as Hutchinson.

And then there’s Harry Lloyd as Baines. It’s an excellent villain performance bolstered by some excellent direction and camera work (the zoom in on his nose when he smells the Time Lord exposed by the open watch is bizarre yet slightly disturbing). Harry Lloyd was everywhere at the time of this story. He was a regular in Robin Hood, as Will Scarlet, and would go on to appear in the first season of Game of Thrones (only to meet a sticky end before it reached the finale). He really seemed like his star was in the ascension. But I haven’t seen him in anything for ages. Now admittedly, he’s probably done lots of stuff I just haven’t watched – or he’s doing loads of theatre or something, but it just struck me watching this again how prominent he was at the time compared to now. (Compare this to Thomas Sangster, for example, who continues to appear in prominent projects such as The Maze Runner films, and seems to have made the difficult transition from child actor to adult without too much trouble).

The Family make for effective villains (invisible spaceship; green glow; odd head movements; an off-kilter way of addressing each other) although their background remains a little vague, probably because the script is more concerned with the Doctor’s new life and Martha’s plight than with fleshing out this mayfly-like aliens in need of the Time Lord’s body.

Human Nature and The Family of Blood also has a top-notch Doctor Who monster – the Scarecrows. Not an original to Who monster by any stretch but still an effective addition to the TV canon (of course, monstrous scarecrows make an appearance in the comic strip The Night Walkers, sent by the Time Lords to retrieve the Doctor after the events of The War Games and in the novel, The Hollow Men (which when I read, I couldn’t picture the scarecrows in it as anything other than those from Human Nature)).

They are appropriately scary (their faces are horrific) and the scene where the farmer sticks his arm straight through the middle of one is almost horror film-like in its set-up. The way they walk, though, does seem a little over-choreographed (although I wonder if this is more to do with too much exposure to the behind the scenes work of Ailsa Berk, the series very-own choreographer. I can see the ‘design’ in the way they move which momentarily took me out of a couple of scenes).

The 1913 setting of this story is really the first time in this period of my marathon that I’ve really felt like the era has been nailed. Obviously this is helped by being televised but the script also pays close attention to how life was with the impending war looming on the horizon. The period detail is beautiful. The clothing and set dressing are, appropriately, drab, echoing the seriousness of this time. The scene on the little street with a piano in danger of squishing an innocent babe is packed with little details from the Doctor’s outfit, to the pram being pushed by the Edwardian woman , the shop fronts, the piano and the clothing of the men attempting to lower it to the ground.

The dance at the village hall is decked out with extras who feel of the right period and the small, unassuming community feel of it is perfect in emphasising the life the Doctor has become accustomed to in his attempt to hide from the Family (there’s a lovely little bit in the Doctor Who Confidential that accompanied this story where a member of the crew reminds the extras that they are not trained dancers, just ordinary people having a dance and therefore they don’t need to be particularly good at it).

But the real period feel comes from the spectre of World War One. The scenes actually set in the trenches with Latimer and Hutchinson are well-staged and despite being very short, evoke the period effectively. But the true art is in the scene where the school boys are forced to gun down the scarecrows attacking the school. John Smith’s call to arms, the boys rushing around being asked to behave like soldiers when they are little more than children is heartbreaking. The script’s decision to have the boys cry whilst firing is, arguably, a little on the nose, but I think it is a realistic depiction of how children would react to the situation. John Smith, frozen, at their side, unable to fire a gun himself, adds to the dichotomy between duty, fear and manliness. All the seeds for this are sown in earlier scenes where the boys train in the art of battle.

The ending of The Family of Blood is interesting. For the main story, we have the Doctor condemning the Family to living deaths. It’s spooky and unsettling (particularly Daughter of Mine trapped in every mirror). It also foreshadows where the 10th Doctor would go, as a character, in Series 4 and the Specials. In contrast is the story’s coda. It sees us jump forward in time to what we presume is the contemporary year 2007. It is Remembrance Sunday and an aged Latimer sits in a wheelchair by a war memorial whilst a (lady) vicar speaks. Around them are various military types – although mainly what I assume to be members of a Combined Cadet Force – the kind that exist in a lot of modern schools. It’s interesting that these are included as they mirror what the boys were being expected to do in 1913 – train for battle. Although modern CCF’s may be a little more laid back (although I have friends involved still in the organisation and their tales of outdoor survival and route marches don’t tempt me to become involved even slightly) it is a definite parallel.

It’s an emotional scene and I admit I did choke up a little watching it. Latimer, the Doctor and Martha are all wordless but much is said in the short scene as Latimer clutches the Doctor’s pocket watch (bequeathed to him when the Doctor and Martha left 1913).

Human Nature and The Family of Blood serves as an effective prelude into my marathon’s exploration of World War One and is rightly considered a stand-out story of the modern series and, frankly, of the whole 50-odd year run. The script, performances, direction and production design all contribute to make something wonderful.